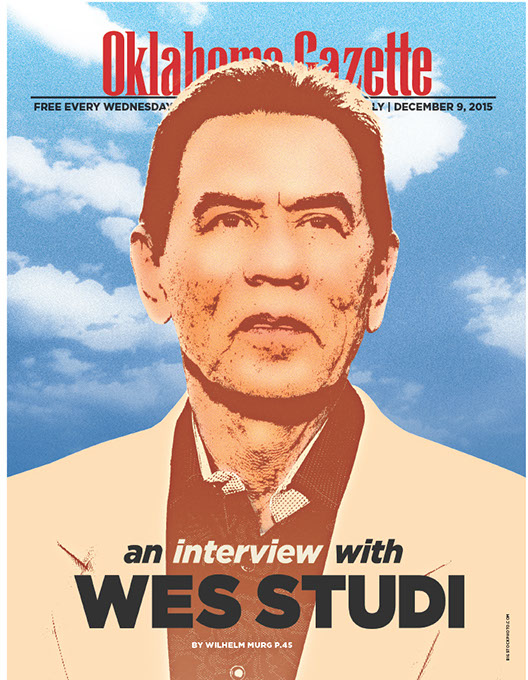

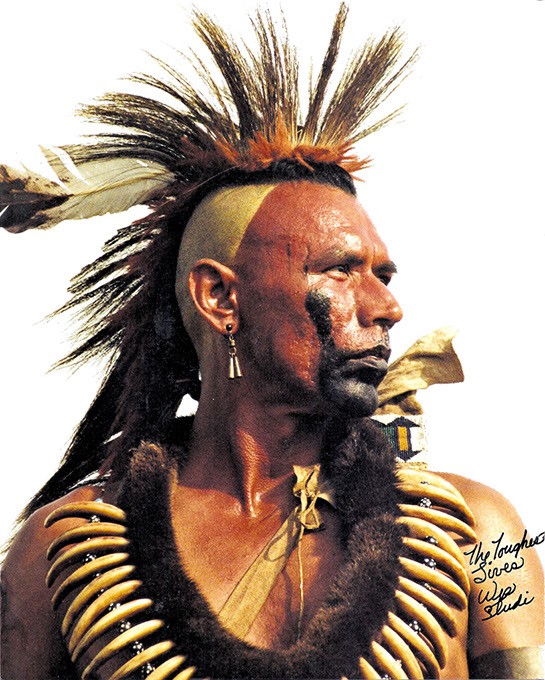

Wes Studi stars in the new Steven Paul Judd short comedy film Ronnie BoDean. It centers around the title character, who is a combination of anti-authority Native American film hero Billy Jack — the returning Vietnam vet who knows karate — and that dude who walks into the bar with an attitude that you either deal with or you move out of his way.

Judd set out to create a cool Indian anti-hero who possesses as much nobility as any of Studi’s more “traditional” roles as 18th- and 19th-century Indians — only this is updated for 2015 and sets him in a world of beat-up muscle cars and cheap housing in contemporary Norman.

But what might be most compelling about the project are the reasons he agreed to do it.

“Steven and I talked about the portrayal of Native Americans, and we talked about how we were either portrayed as really good or really bad, but not a lot of in between, where life really happens,” Studi said during his recent interview with Oklahoma Gazette.

“He told me about this character, and I quickly saw that this is real life; we all have a relative who is like Ronnie BoDean. I felt like this really gets to the heart of the matter of what Indian life is all about in these here United States, and I liked the idea. And why not? It could build into something more, and it is being accepted very well.”

Studi’s involvement was a coup for Judd, who seems overwhelmed that such an iconic Native actor is playing the role.

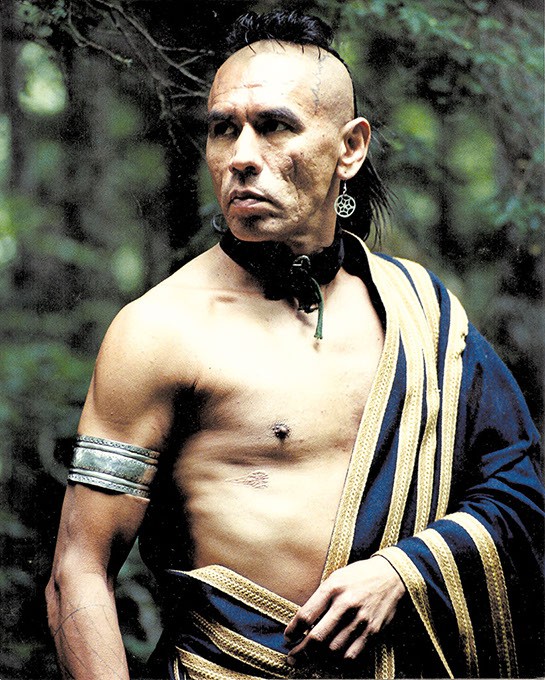

“It was amazing. If you are a Native person, you know who Wes Studi is; you’ve seen him. He’s Magua, you know, ‘Why does Magua hate the grey hair?’ You know?” Judd noted, referencing Studi’s classic performance in Michael Mann’s 1992 adaptation of The Last of the Mohicans.

And “icon” is not too strong a word. While there are many fine Native actors working today, including many of Studi’s contemporaries like Gary Farmer and Graham Greene, it was the string of monster hit films in the early 1990s, including Dances with Wolves, Last of the Mohicans and Geronimo: An American Legend, that made Studi the face of Native America.

He even spent less than 60 seconds onscreen as Jim Morrison’s Indian vision in the 1991 movie The Doors and became iconic to a generation of stoners via VHS tapes.

“I was barely in it,” Studi said. “I have tried to get it off my IMDB profile.”

Judd recently returned from showing Ronnie BoDean in Europe and has been hitting film festivals around the country.

The work also was shot so it could be used as a TV show pilot or a demo reel for a feature film. It will be available for download during the week of Christmas.

‘True light’

Native film has been going through a transition over the last quarter century, beginning with the release of Powwow Highway in 1989, in which Studi appeared in a small role. It was his first film.

That also was the first Native American-made feature to show Indians as contemporary people living in the modern world, as opposed to being characters from the 19th century or earlier. Since that time, as digital technology made filmmaking more affordable, a full-blown movement made of Native filmmakers who created their own statements on their culture, including Oklahomans Judd and Sterlin Harjo, as well as Chris Eyers, Jeff Barnaby and Sydney Freeland, developed, and it is a direct result of the activism Studi was involved in when he got back from Vietnam 46 years ago.

“Contemporary Native life, the idea of us getting out of leather and feathers and into jeans and T-shirts, that’s the one area that has been the least explored about Indians in film,” Studi said. “These films show us as part of the real world today, and I think that’s an important thing not just for our youth, but even for those of us as adults and everyone and everything in between. It’s something we’ve talked about for a long time, making our own films that reflect a more true light of who we are in the world.”

Political change

To understand Studi as an actor, one needs to only look at his life. Studi lived a very common Native American story for people of his age. Born in Nofire Hollow, Oklahoma, he was raised in a household that spoke only Cherokee, was sent to an orphanage to learn English, ended up in the army in Vietnam at the height of the war and came back during the flowering of the social revolutions of the 1960s and early ’70s that got him involved in some of the most famous takeovers and confrontations between the federal government and American Indian Movement, aka AIM, a vocal civil rights organization founded in Minneapolis in 1968.

Studi described himself as being “deposited at” the Murrow Indian Children’s Home, an orphanage for Indian youth in Muskogee, when he started school.

He said his family felt he could get a better education there than he could in a one-room schoolhouse, the kind that were still in operation in rural communities at that time.

“I had seen white people before; I knew they were different to a certain extent. I didn’t equate it with being a part of a different world or whatever; the language was what was different about us,” Studi said. “Most of my family was very mistrustful of [white people], and they told me to be mistrustful of them as well. I went into the world and learned English, but then I went home and I was speaking English in a Cherokee household, and it just didn’t work, so I had to relearn Cherokee. Then I went back to school and began to relearn English, and it was like that from then on.

“A part of my life after that was being totally surrounded by non-Indians, and many times, I was the only Native American kid in the class because we lived in small towns,” Studi continued. “From there, I went to Chilocco Indian Agricultural School [in Newkirk], and there were some Cherokee students there. They seemed to feel that we shouldn’t speak Cherokee, so I didn’t get much of a chance to speak Cherokee there either. In any case, I have held on to the Cherokees’ language for the larger part of my life.”

Studi’s knowledge of both languages would come into play years later, after the political change in the Native community. In the early 1980s, he wrote two books for bilingual education for the Cherokee Nation: The Adventures of Billy Bean and More Adventures of Billy Bean.

The political change that would bring about bilingual education, teaching Indian children the language their parents were forced to give up, also is a direct result of 1960s social protest movements to bring attention to Native American rights.

After school, Studi joined the Army and served a tour in Vietnam with the 9th Infantry Division in the Mekong Delta. Due to the unpopularity of the Vietnam War, some people spat on, threw garbage at and taunted returning soldiers who had honorably served their country; it was a shameful moment in American history.

However, within Native American communities, often built around warrior societies, the majority of returning Indian veterans were welcomed and cheered by their communities as returning warriors.

“I think there was alienation, a feeling of having no appreciation from the general public, but the Indians took us back,” Studi said. “While the general public was extremely down on soldiers who were coming back — [shouts of] ‘baby killer’ and all of that crap — it only added to an existing alienation we were all feeling. AIM was a movement that was taking shape, and it looked like it could be successful in what it was purposing to do, which was to start a dialog. This was a time of social unrest throughout the nation, and we had our grievances for much longer than the protest movements certainly had. It was quite a time to live in.”

‘Ordered out’

Studi threw himself into Native American politics. He joined AIM and, in 1972, was part of the Trail of Broken Treaties march on Washington, D.C., in which protesters briefly occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs building.

“It’s kind of a comedy of errors,” Studi said. “We were denied entrance to the building as a group — they told us to pick our leaders and they would meet with them. But the D.C. police got involved because of the huge crowd around the building, a fight broke out at one of the doors and the police were overwhelmed. The doors opened and everyone came in, spread throughout the whole building, and wondered, ‘What’s next?’ There was no plan to actually take over the building; it was just a big mistake.”

After the building takeover, AIM members returned to their communities and worked on local projects while they waited for the next big confrontation. During that time, Studi participated in the AIM takeover of the City Hall of Hammon, Oklahoma, where Indian people were systematically charged more for consumer goods than whites.

Then the call came for reinforcements during the takeover of Wounded Knee, South Dakota. The chief was making decisions without consulting the counsel and instated his own militia on the reservation to silence his enemies. To call attention to the problem, 200 AIM members occupied the small town for 71 days.

Studi was in a caravan of Native Americans that converged on Rapid City, South Dakota. While the FBI and U.S. Marshalls held a perimeter around the reservation, reservation residents knew the land, and people, supplies and weapons were being smuggled past the perimeter throughout the ordeal.

“We went inside, and then we were asked to go back out and bring more stuff in, and on the way out, we were arrested and spent a little time in their jail,” he said. “We were ordered out of the state by both the federal and the state authorities, so we were escorted to the state line, and off we went, back to Oklahoma. We continued to support them as well as we could.”

Studi began writing for Tulsa Indian News, a mimeographed, legal-sized newsletter about AIM concerns, where his first published his Billy Bean stories.

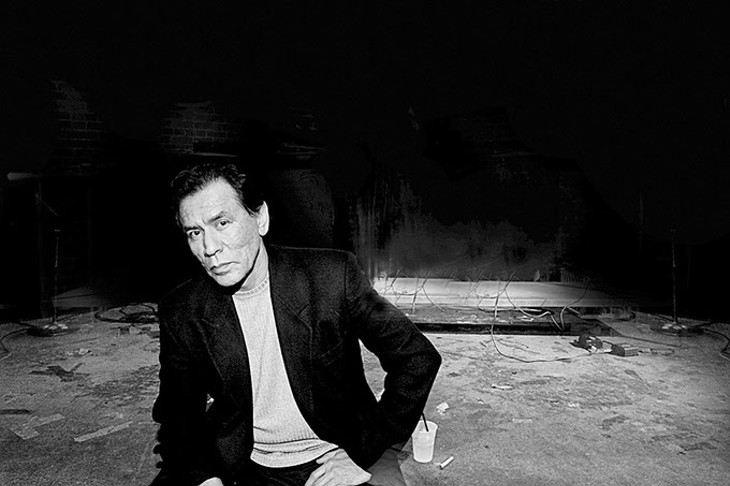

He also became involved with the American Indian Theater Company in Tulsa, which also was an echo from those days of social protest.

He was first noticed as an actor in 1984, in the Tulsa production of Black Elk Speaks. As it was one of the few, if not the only, Native American theater companies at that time, Nebraska Public Television came to Oklahoma to put casts together for some of their productions and hired Studi for various projects, which lead to his moving to Hollywood to become the star he is today.

Authenticity

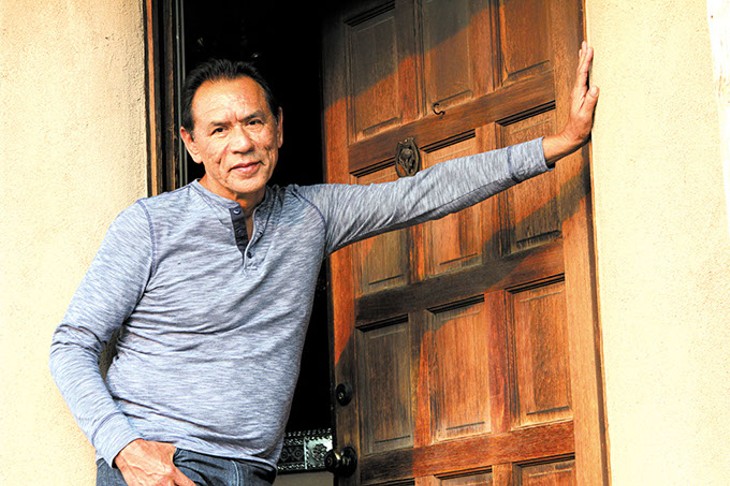

Studi’s authenticity cannot be questioned. When you see him as Ronnie BoDean, those experiences, living the rather taxing life his generation of Native Americans had to endure, inform his performance. You can see it in every move, from the swagger when he announces to his opponent that he is about to kick his ass to the uncomfortable jokes he uses to cover up his poverty to the children in the film.

The irony of Ronnie BoDean is that while it is, without a doubt, the most lighthearted of all the contemporary Native films out there, it might also be the most subversive. Studi and Judd have taken these experiences and ideas and boiled them down to 12 minutes.

These days, there’s a lot more to being an Indian actor than just getting shot off a horse.

Learn more about filmmaker and artist Judd in Oklahoma Gazette’s Nov. 25 cover story, “Andy Warriorhol,” at okgazette.com.

Learn more about Studi at wesleystudi.com.

Check out this ICON Award interview with Studi at 2014's deadCENTER Film Festival:

Print headline: Studi’s ‘radicalization’, Shunted from an orphanage to Vietnam to highly politicized fights for civil rights, Oklahoma actor Wes Studi also blazes a trail for Native American filmmakers and actors.