Completed in 1917, Jacobson House, located on the University of Oklahoma (OU) campus in Norman, was an epicenter of Native American art in the early 20th century.

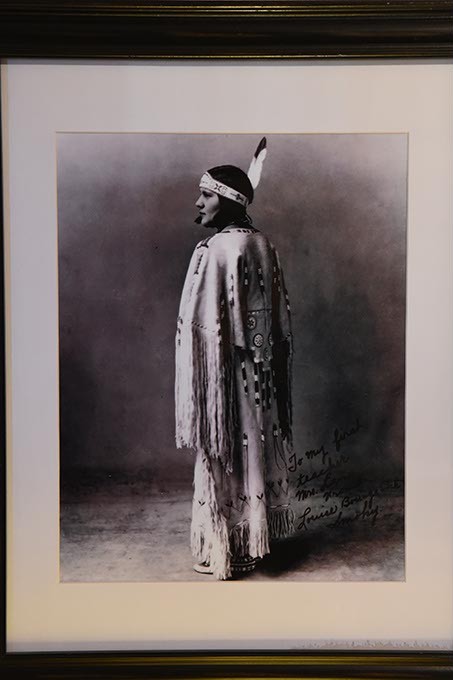

The Kiowa Six (formerly known as the Kiowa Five), were key figures in developing flat-style, the dominate painting style of Native art in the mid-20th century. The group used the structure as a residence and studio.

The Jacobson Foundation formed in 1986 when the university was planning to level the house for a parking lot. The foundation succeeded in placing it on the National Register of Historic Places, and it is now on the Oklahoma Historical Society’s Landmarks list.

Now called Jacobson House Native Art Center, its goal is to promote Native art and culture, and it celebrates its centennial next year.

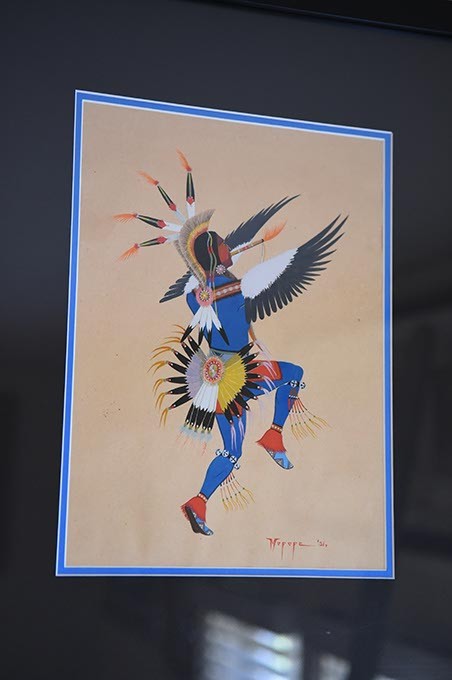

The house was built and designed by artist and educator Oscar Brousse Jacobson, who was director of OU’s School of Art from 1915 to 1954. In the spring of 1927, he created a “special,” unaccredited program at the school for four Kiowa artists: Spencer Asah, Jack Hokeah, Monroe Tsatoke and Stephen Mopope. When they returned in 1928, Lois Smoky joined them, but stayed for only one semester and was replaced by James Auchiah.

Though it included six artists, the group has traditionally been known as the Kiowa Five because when Smoky left and Tsatoke joined, they remained five in number.

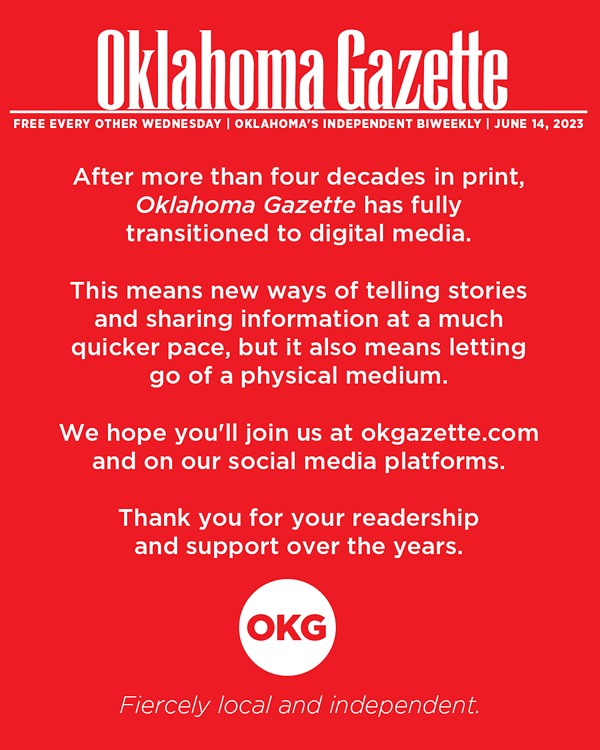

Smoky has one painting in the historic 1929 portfolio Kiowa Indian Art, the first printed collection of the group’s work, but her contribution was relegated to the footnotes of history for decades, like the work of many women of all races.

In retrospect, Smoky was perhaps the most revolutionary artist of the quintet for three reasons: She was Native American, an artist and female. It becomes even more astonishing upon realizing Smoky painted figuratively when, within the Plains Indian tradition, men generally painted figuratively and women painted abstract designs.

“Lois Smoky was a trailblazer. She picked up that brush; she was educated in a formal institution,” said Tracey Satepahoodle-Mikkanen, Jacobson House executive director. “I don’t think it is correct for the Jacobson Foundation to use the term Kiowa Five.”

Satepahoodle-Mikkanen, who is Kiowa and Caddo, approached Kiowa tribal elders, leaders, the museum and members of her own family to get their opinions on changing the term to Kiowa Six so Smoky’s work is included in the public consciousness.

“I was only granted that permission by my elders if I added the caveat ‘…formerly known as the Kiowa Five,’” Satepahoodle-Mikkanen said.

In an ironic twist, Smoky’s work is the most valuable out of the six artists’ paintings because she painted for only one semester. She exited the art world to start a family and later devoted herself to beadwork.

‘Contaminated’ art

The Kiowa Five are important for more than the acclaim they received; their place in history connects their elders, the warriors who fought on horseback, to today’s contemporary Indian artists.

The tradition of figurative art painted on hides goes back to pre-contact days, but the major evolution occurred at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, at the end of the Red River War in 1875. Seventy-one Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho and Caddo warriors and one woman, the supposed leaders of the resistance, were imprisoned there.

The fort was run by Richard Henry Pratt, who endorsed reeducating Native Americans so they could assimilate into white culture in a practice some now call cultural genocide.

In the process, Pratt introduced new art materials — pencils, ink and paper in the form of used ledgers — to a group of captured warriors who would go on to become noted artists. The belief that they would be reeducated ultimately backfired as the Indians preserved their traditions and designs and built on them with the simple materials they were given.

However, the bigger change at that stage of Native art had even more ramifications.

Oklahoma Gazette spoke with Cherokee artist, writer and educator Kevin Warren Smith, who has worked as a consultant on exhibitions for Jacobson House. He also worked with the collections of Philbrook Museum of Art and Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa. Though Smith is not a member of the tribe, he has Kiowa heritage.

“These are warriors who came from the old days [and] all of a sudden make the big jump to being European-style artists because they are signing their names and selling their pieces,” Smith said. “That’s a huge jump in Native American art. … Before, they were making these simple drawings on hides and hide shirts and they were telling stories or making emblems, but [due to outside involvement] they got more ornate in their drawings and they competed with each other. They could see who was selling the most and figure out why … and they would change their art. They became ‘artists,’ in the European sense, when they did that.”

Two of those Kiowa artists who were held captive at Fort Marion, Silver Horn and Ohettoint, were great uncles of future Kiowa Six members.

After their release, they came back to Oklahoma with the new art form they developed and taught it to younger artists, who then started doing it on their own.

The young Kiowa artists went to Catholic school, they had contact with agency people and their talents were encouraged.

“They make it to Jacobson, and he takes them to the next big jump,” Smith said. “They call it ‘easel painting,’ even though a lot of it is done flat, on a desktop, because it is done with watercolor and tempera, but they become painters; they are no longer just drawing.”

Ironically, white artists and educators were attempting to keep the Indian art “pure,” free from outside influences, such as contemporary European art. In the process, however, these educators with the best of intentions inadvertently “contaminated” the Kiowa Six by keeping them from experimenting with outside influences and critiquing and instructing them with an eye toward the commercial market.

Smith noted that it was not just Jacobson, but also Dorothy Dunn, an educator who established The Studio School for art instruction at the Santa Fe Indian School, teaching students — including future acclaimed artists Allan Houser, Harrison Begay and Oscar Howe — to paint in flat-style with no deviation. Later in life, Houser, one of the more experimental artists to come out of the school, famously criticized Dunn as lacking originality and creativity.

Trips were arranged for the Kiowas to go to Santa Fe to see what was happening at Dunn’s school, so the style became homogenized, to some degree, due to their teachers’ influence.

“It is still a way to tell stories, but it’s changed a lot,” Smith said. “You might still have a war scene where one warrior was attacking another warrior, so in a way, it is still related to the old-time paintings, but something has been changed. Being European artists, they want their educators to be pleased with what they do.

“Jacobson keeps them focused on a certain way of painting. He wants to see certain things and doesn’t want to see other things. A couple of these guys were interested in trying other European styles, but they were told to kept with the flat, representational style that is not illusionistic, so there is no 3-D shading or anything like that.

“That’s when people got comfortable saying that flat-style art is Indian art, and Indian art is flat-style. I don’t believe … that these institutions were guiding them so much that they were creating an artificial Indian art, that it was coming from non-Indian educators. I don’t think it is quite that simple anymore.”

Smith shared several examples.

“I’ve studied the pieces for so long now, I can tell Tsatoke, and Mopope especially, these guys found a way to work within the parameters yet go beyond to make epic pieces,” he said.

As commercial Native American art developed over the century, there was a movement against the flat-style in the 1960s and 1970s by heirs and students of these artists who were attempting to move beyond it.

The rebellion took hold when a painting by Oscar Howe, who won the grand prize in an earlier Philbrook Indian Annual, was rejected by the 1958 annual committee for not adhering to the stylistic parameters the Philbrook imposed on Native American art.

“When the ’60s came along and there was the movement against flat-style and other artists were trying to go beyond it, each Indian artist was saying, ‘I’m an individual,’” Smith said. “In certain situations, if I go to a gourd dance, nobody’s an individual; everybody has a place, and we’re all just pieces of the same thing.

“It always seemed ironic to me that they went from calendar counts and designs on their shirts to suddenly signing their names and selling to tourists and hanging and having exhibitions. … If they want to put tribal references in, they can, but they don’t have to.”

However, Smith said, those changes didn’t extend to the Kiowa Six.

“Their job was still to paint their tribe’s ceremonies and activities,” he said. “When the ledger art happened, it was a huge mental jump because now, you are not a tribal member; you are an individual, because America is about the individual. Tribally, it wasn’t like that. Once you sell pieces in a gallery exhibition, you are an individual artist.”

The process shows how even if gallery art is an outcome of cultural assimilation, the imagery, stories, beliefs and spirit of the Native people are so strong that they have not only adapted and survived in that system, but prospered, grew and live on for future generations.

Jacobson House today

Satepahoodle-Mikkanen said that though they came from vastly different backgrounds, the Kiowa Six and Jacobson built a bridge of mutual respect for each other that allowed them to work together.

Her job is to extend that bridge to both Natives and non-Natives who want to learn more about past and present Native American cultures.

“I use the word ‘multifaceted’ because when you say ‘Native Art Center,’ that includes an array of different programs and cultures,” Satepahoodle-Mikkanen said. “We hold cultural classes, we have shawl-making classes, beadwork classes, how-to classes. The other side of that is we hold cultural events and classes, and one of those is the drumming that we pull together that allows students, both female and male, to come together and sing and learn about the protocol and the songs of our people.”

As a tribute to the legacy of the house, the venue also promotes classic Native American art and serves as a showcase for contemporary Oklahoma Indian artists. It also serves as a meeting space for the Native American organizations on the campus.

“We hold loose ties to those students to help them educate themselves and to be a resource center for them,” she said. “A lot of our students come from a small rural setting, and to be dropped into a large university setting — going back to Lois Smoky — it can be very confusing and disorienting. So if you just want a place where you can grab a sandwich or print a paper or you might need to do some research, we provide that place.”

For more information, visit jacobsonhouse.org.

Print Headline: Artful evolution, A group of art students in Oklahomachanged the course of Native American art.