The last remaining examples of the first depiction of black comic book heroes sat forgotten in storage for decades.

Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s preeminent black newspapers, published a series of color comics featuring four black heroes from 1950 to 1954, a full generation before the first black heroes appeared in the mainstream.

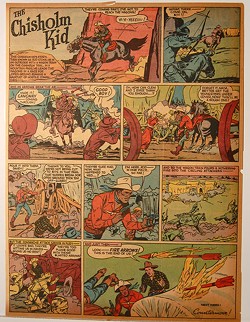

One of those heroes, The Chisholm Kid, is on exhibit at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, 1700 NE 63rd St., through Sept. 21.

The color comic insert that also included Guy Fortune, a U.S. secret agent; Mark Hunt, a private investigator; and astronaut Neil Knight was a collaboration between the Courier and publishing company Smith-Mann & Associates whose partner Jon Messmann was good friends with the editors of the Courier, the Vann family.

After the insert’s color edition ended in 1954, it continued in black-and-white for another two years before being discontinued with nearly all examples of the revolutionary depiction lost to time, until 2014.

Hidden treasure

Alan Messmann, Jon’s son, discovered galley proofs of the comics after moving much of his late father’s belongings from New York City to Little Rock, Arkansas. After months of unpacking, Messmann and his wife had one final box. He opened it to find a big canvas cloth surrounding a giant leather-bound case sealed in cardboard sheets. The colorful proofs shined back at Messmann like a historic jewel.

“They were beautifully preserved, and many of them looked like they could’ve been done a week ago,” Messmann said. “I immediately thought, ‘Oh my gosh! These need to be in the public’s eye. It’s a whole different depiction of culture from this time period.’”

Messmann eventually found a home for the comics at the digital Museum of UnCut Funk, which houses many comics and images from the late 1960s and 1970s, but found the series from the Courier to be unprecedented because of its limited circulation.

“They were revolutionary and ahead of their time, and other copies didn’t exist,” said Loreen Williamson, Uncut Funk’s co-founder. “A lot of the things we have didn’t come until have the civil rights protests. It’s critically important for these comics to get their historic due and to know that the depiction of black heroes and heroines pre-dated the civil rights movement.”

National Cowboy Museum will shine light on the breakthrough of The Chisholm Kid while also commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Chisholm Trail, the hero’s namesake.

After the Civil War, as many as 6 million cattle were located in southern Texas. Drovers wanted to get the cattle out of Texas and up to Kansas City and Chicago, where the beef could be sold for as much as ten times what it could in Texas, according to Don Reeves, the National Cowboy Museum’s curator and McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture.

Many of the drovers on the trail from south Texas through current-day Oklahoma and into railheads of Abilene, Ellsworth and Dodge City, Kansas, were black, Reeves said.

“One comic in particular, The Kid is undercover on the Chisholm Trail on a wagon and they’re attacked by Indians,” Messmann said. “It’s really cool to see it all come together with the anniversary.”

Some of the heroes represented in the Courier inset, including The Chisholm Kid, were drawn by white artists like Carl Pfeufer, who got his start at Marvel Comics. Pfeufer illustrated The Chisholm Kid and was one of the original artists for Marineman, which later became Sub-Mariner.

“The Chisholm Kid seeks out justice and rights wrongs,” Williamson said. “He is the equivalent of the Lone Ranger or Hopalong Cassidy. He’s firmly grounded in Western comic heroes and brings a perspective of what it means to be a cowboy and doesn’t alter it because he is black. You don’t see another black cowboy in comics until the 1960s, and he predated black heroes in animation by 20 years. It’s fascinating when you put it in context.”

Messmann said his father always had a penchant for making things unique. The comic insert gave Smith-Mann one his first opportunities to use four-color separation, and the Courier was the first black newspaper to publish in color, according to Messmann.

The ideas for the comics were born between dinners of Jon Messmann, his wife and the owner of the Courier.

“My mother told me that they’d go to dinner at these fancy restaurants and have to call ahead and tell them that they were bringing a black couple, even in New York City,” Messmann said. “It’s crazy to think about now.”

Western kaleidoscope

The exhibition featuring the trailblazing Chisholm Kid is one of many at the museum with a commitment to the “kaleidoscope” of the West, according to Reeves. Buffalo soldiers; black rodeo champions; and Herb Jeffries, “the Bronze Buckaroo,” Hollywood’s first black singing cowboy, are among those exhibited.

“It’s about presenting an open window of the West,” Reeves said. “The Chisholm Kid is an example of an urban Pittsburgh culture adopting a Western hero and a really cool vignette. It’s not so much what [The Chisholm Kid] did, but who [he was]. The fact he could become a positive figure and hero for young people who didn’t have any heroes who looked like them, really just The Bronze Buckaroo.

“Fictionalized television and B-Westerns generalized everything and that’s how people who aren’t from here started believing all cowboys looked and dressed like Gene Autry or John Wayne.”

The exhibition is the first featuring The Chisholm Kid in full and large display. Messmann is hoping to make the trip from Little Rock with his 90-year-old mother.

“I think it’s fabulous and something that is needed today as much as it was in the 1950s,” Messmann said. “It was so inspiring for people who looked at those comics, and now people will be able to see it and say, ‘This is really cool.’”

The museum is open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday-Saturday and noon-5 p.m. Sunday. Admission is free-$12.50. Visit nationalcowboymuseum.org.

print headline: Comic Gold, A Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum exhibit highlights forgotten comics of The Chisholm Kid found in boxes.