Standing Their Ground: Warrior Artists

through Oct. 31

Exhibit C

1 E. Sheridan Ave., Suite 100

exhibitcgallery.com

405-767-8900

Free

Charles Guerrier took his nephew to a bar in 1962 to show off the freshly minted Marine to the local cadre of combat veterans. Harvey Pratt had always looked up to his war hero uncle, a heavily decorated Marine who served in World War II and was just the latest in a long line of proud warriors to come from their Cheyenne and Arapaho families.

“He’d been shot up good, wounded quite often, missing in action,” Pratt said. “I always heard stories about him, and when I came back from training and was about to ship out to Okinawa, he invited me over.”

Two others whom Pratt had never met joined them, and he only remembers them as a first sergeant and master sergeant. Throughout the night, veterans stopped by to pay respects to the strangers, buy drinks and leave money. Pratt didn’t question it; instead, he just took in all the war stories and advice passed across the table.

“I was sitting there with three old warriors with ribbons all the way up to their collarbone,” Pratt said.

At the end of the night, the two strangers offered to set Pratt up with a ride to Dallas aboard a Marine commandant’s plane, which Pratt first thought was a joke but accepted all the same.

Pratt would later learn that those two strangers were Medal of Honor recipients, an honor so significant and rare that even generals are obligated to salute recipients, regardless of rank. Inspired to join their warrior ranks, Pratt volunteered for the 3rd Recon Marine Battalion in 1963 on a mission to Vietnam, two years before the American combat troops officially arrived.

Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian recently selected Pratt’s Warriors’ Circle of Honor concept design for the Native American Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., which breaks ground this September and opens Veterans Day 2020.

"We all have traumatic experiences,

tweet this

veteran or not, and these

stories need to be brought out."

— Monty Little

Pratt was also selected for a group show of Native American veteran artists titled Standing Their Ground: Warrior Artists at Exhibit C along with Enoch Kelly Haney, a member of the Seminole tribe who served in the National Guard, and Monty Little, a member of the Navajo tribe and also a Marine.

“American Indians serve in their country’s armed forces in greater numbers per capita than any other ethnic group, and they have served with distinction in every major conflict for over 200 years,” wrote Kevin Gover, director of Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, in a piece for Huffington Post.

Little said the warrior spirit and ceremony of the Navajo tribe made transition into the military culture easier for him.

“The mental part of the Marine Corps as well as the discipline was already instilled in that traditional Navajo lifestyle,” Little said. “We wake up early in the morning and run to the sun to greet the day. Towards the end of the day, we reevaluate ourselves as a discipline. A lot of Navajos go into the services because it has been passed down generation to generation. My grandpa went, as did his brother, who became a Code Talker (in World War II), and that paved the way for future generations.”

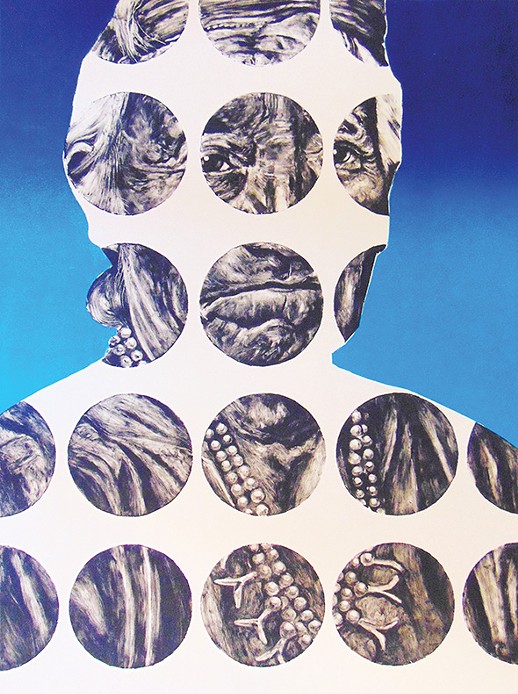

Little said he is featuring his Precursor series, which hints at the large body of work he plans to create as he continues to grow as an artist. He calls it his introduction. The paintings delve into his battling identities: the traditional life of the Navajo and the modern American experience. His combat experience in Iraq only heightened that struggle.

“We all have traumatic experiences, veteran or not, and these stories need to be brought out,” Little said. “It is a good way to heal, to project all these feelings through artwork. You are letting it out, letting it be seen, letting it be critiqued.”

Tom Farris manages Exhibit C and curates the exhibits along with Kelley Lunsford. Though the gallery was originally envisioned to represent Chickasaw arts and culture in the heavily traveled Bricktown district, Farris said that artists have been increasingly brought in from other federally recognized tribes. According to Farris, Standing Their Ground was an opportunity for Exhibit C to explore the significant cultural importance and impact of military service within the Native community.

“There is a deeply rooted connection to the warrior spirit in Native culture, that ability to be a protector,” Farris said. “There’s a long history of proudly serving in the military. We always have an opening at this time of year, so it made sense to put together a veterans exhibit as a nice gesture to honoring the military service that Native Americans have provided.”

Farris added that Haney will be known to many Oklahomans as a former state senator and principal chief of The Great Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, who is also a painter and the sculptor behind “The Guardian,” which sits atop the state Capitol.

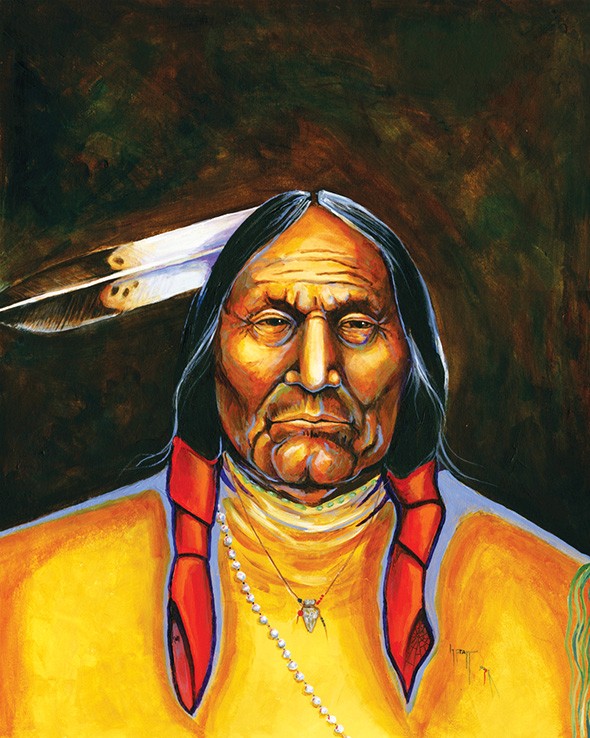

Like Haney, Pratt’s service didn’t end when his military career wrapped up. He went on to work for the Midwest City Police Department and then with the Oklahoma Bureau of Investigation as a forensic artist. In his own art, Pratt explored contemporary and classic themes of Native American ceremony and heroism.

In 2000, Pratt began his battle with cancer, which would repeatedly return over the years, a result of that brief stint in Vietnam in 1963 as he roamed jungles poisoned with Agent Orange. Because that mission was kept secret, Pratt said his own record didn’t have any evidence of him ever going to Vietnam and it was only after his commandant’s record was opened that he could confirm his exposure to the toxin.

“I’ve always had some issues, but I thought they were normal, just the way it was,” Pratt said. “When I realized what had caused it, I contacted three other guys I served with and found out we’d all contracted cancer at the same time. I was fortunate enough to have good insurance and get an early diagnosis, so I beat it. Two of them are now gone.”

Pratt said the way veterans talk about the long-term ramifications of combat has changed with the newest generation of veterans being more open and assertive about their stories being told. Little said he is part of Dirty Canteen, an art collaborative composed of veterans using their artwork to bridge the divide between military and civilian cultures. Little said he has received a lot of support because his art allows civilians a glimpse into the veteran experience.

“Veterans have a lot to say, and people are interested in hearing these stories from a different perspective, in a creative way,” Little said. “It can be scary, but it is their experience and we need to give veterans a chance to do this work.”

Visit exhibitcgallery.com.