In Oklahoma City’s increasingly competitive booking market, The Jones Assembly recently reeled in a really big fish.

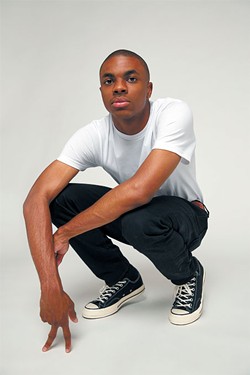

Vince Staples, a 24-year-old rap star hailing from Long Beach, California — a city with a hip-hop progeny that includes 213 triplets Snoop Dogg, Nate Dogg and Warren G — was announced in mid-February as a surprising but welcome addition to the Film Row restaurant and venue’s performance schedule.

Staples is set to play 7 p.m. March 8 at The Jones Assembly, 901 W. Sheridan Ave. Tickets are $27.50-$500.

The young emcee reached a new level of popularity and critical praise after the release of sophomore full-length LP Big Fish Theory in June. The album includes guest appearances by Ty Dolla $ign, Juicy J, A$AP Rocky and Kendrick Lamar. Staples also appears on the song “Opps” on Black Panther: The Album, an official soundtrack to the blockbuster Marvel movie.

Staples first appeared on music radars as a periphery figure in the Odd Future hip-hop collective’s internet-fueled rise in the early 2010s. Though not an official member of the group, he was most known as a friend and musical collaborator of teenage rap prodigy Earl Sweatshirt.

Though Staples is now firmly established as a solo artist, he still carries some stylistic ties with his millennial Odd Future contemporaries. Staples makes his OKC appearance straight off a tour with the collective’s ringleader Tyler, the Creator.

At the same time, Staples has used his first two solo albums to set himself apart as an artist not only unique to other rappers his age, but to all of hip-hop. On his Summertime ’06 debut in 2015, the emcee found middle ground between what would be considered the traditional gangster rap of his West Coast forerunners and the type of self-aware reflectiveness that comes from youth suddenly made aware of the wider world around them. Expert production from No I.D. also gave Staples a dark but understated platform that put his lyrics front and center.

One of Staples’ biggest advantages as an artist might be a refined taste in beats. Big Fish Theory breaks away from anything that could be called a conventional hip-hop instrumental. Whereas Summertime was purposefully subdued, Big Fish channels noisy Detroit techno that often commandeers the listener’s complete attention. Hip-hop is known for its rumbling bass, but Big Fish takes the concept to a new extreme.

On its surface, the album does not sound like a hip-hop album, but reviewer Joe Madden of New Musical Express pointed out that Big Fish takes sounds invented by black people that are no longer associated with the race and repurposes them to once again fit the aesthetic of modern black youth.

In a 2017 interview with LA Weekly, Staples hinted that his album might represent rap music’s next big wave.

“We making future music,” the artist said. “It’s afrofuturism. This is my afrofuturism. There’s no other kind.”

Shifting focus

Staples also plays a part on Black Panther: The Album, which, in itself, is somewhat of a modern anomaly. The soundtrack was curated by Lamar and his Top Dawg Entertainment label as an accompaniment to the highly successful superhero film. Other big-name artists like The Weeknd, SZA, ScHoolboy Q, Travis $cott, Future and Rae Sremmurd’s Swae Lee appear on the tracklist.There was a time when movie soundtrack albums were not only commonplace, but hot-selling commodities. The concept never truly went away, but it certainly lost steam in the era of high-speed internet, likely due to a combination of factors such as decreased theater attendance, unprecedented access to other kinds of music through YouTube and streaming services and just a general decrease in album sales across genres.

However, the Black Panther album joins the film version at the top of their respective sales charts. The Lamar-crafted project topped Billboard’s top sellers with 154,000 equivalent first-week album sales.

It might be a movie tie-in album, but Black Panther can easily be called a standalone project. Without context, one could easily come to the conclusion that the soundtrack was a well-made, between-albums collaborative experiment by Lamar.

The album’s popularity is fueled by the appropriateness of Lamar to guide Black Panther’s auditory equivalent. The film is the first major superhero movie in the modern Marvel film series to feature a black protagonist and largely black cast, and Lamar is arguably the most vocally pro-black artist in mainstream music.

Staples is also a voice for black empowerment, but often with a focus more firmly set on the future.

Writing about Big Fish in a pre-release Twitter post last year, Staples once again described the album as his attempt at afrofuturism.

“We’re trying to get in the MoMA (New York’s Museum of Modern Art) not your Camry,” he wrote.

Though Big Fish was highly lauded by many music critics, Staples’ sophomore effort was snubbed at the recent Grammys. His public image in recorded interviews is typically a nonchalant, ambivalent and sarcastic one. But when it comes to music, Staples cares deeply about his craft and how it is perceived.

In an interview with NPR Music before the announcement of any 2018 Grammy nominations, Staples said he believed his album deserved recognition not only for Rap Album of the Year but Alternative Album of the Year, Electronic Album of the Year and overall Album of the Year. He argues that the Grammys and some other awards practically segregate black artists from competition by lumping them in arbitrary categories.

“I don’t need any award to tell me that I’m better than everyone else or not better,” he said. “Differentiation is key to me. I don’t really believe in better or worse; it’s subjective. When you find other music that sounds like my music, then you can come talk to me about that type of thing.”

Staples is right in saying that not too many albums sound like Big Fish, which is perhaps to the Grammys’ defense. But if the artist’s vision for Afrofuturism proves to be a mainstream reality in coming years, it will necessitate major shifts to long-standing industry mindsets.

Print headline: Getting hooked; Rapper Vince Staples brings his brand of afrofuturism to The Jones Assembly.