The new face of Oklahoma City is young, well-educated and reinventing the American Dream.

Cities across the country covet millennials, young adults born from around 1980 to the early 2000s, who boost local economies when they arrive and destroy them when they leave.

Look at cities where the economy is growing the fastest, according to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, over the past 2 years: Nashville, Tennessee; Dallas; Houston; Orlando, Florida; and OKC. These cities enjoyed double-digit percentage millennial growth, according to Census data analyzed by real estate information company RealtyTrac.

Cities that saw the biggest GDP declines — Detroit, Chicago, Boston and Cleveland — also experienced at least 10 percent drops of millennial residents.

This data shows that this group, typically defined as between 20 and 35 years old, boosts an economy, but a growing economy also attracts more millennials, creating a chicken-or-the-egg scenario.

“Naturally, millennials are attracted to markets with good job prospects and low unemployment,” said Daren Blomquist, vice president of RealtyTrac.

Whatever the cause and effect might be, city leaders across the nation understand that it’s better to have more young adults living in their cities. It is a goal OKC’s leaders embraced in the past several years.

“Every city out there is trying to recruit highly educated 20-somethings,” Mayor Mick Cornett told Fast Company Magazine in an October article about the city’s recent transformation. “That’s how you drive the economy in this digital age.”

While OKC succeeds in encouraging growth of businesses and infrastructure to attract young adults, it faces many challenges when it comes to keeping them here as they age.

OKC competes with Austin, Texas; New York; and Denver to attract millennials. It also will compete with Edmond, Yukon and Piedmont to keep them as they get older and start families.

Oklahoma?

“I literally got my degree, shook the dean’s hand, walked off the stage and got on the plane,” said Catherine Anadu about graduating from the University of Oklahoma in 2000. “I never thought I would see the state of Oklahoma again.”Anadu’s story was a common one, as students who either grew up here or studied at a local university fled for the greener pastures of big cities that have reputations as young adult culture meccas.

Anadu, who has dual citizenship in the U.S. and Nigeria and spent her high school years in Houston, worked in New Orleans and Denver before moving to New York.

Anadu has a degree in petroleum engineering and received a call from a Devon recruiter asking her to interview for a job in Oklahoma City.

“I was like ‘click,’” Anadu said, mimicking hanging up a telephone.

But the position was intriguing even if the location was not. She decided to visit the city to see what Devon had to offer.

“I took some time to research,” Anadu said. “Even though I am all about being corporate, I read where Oklahoma City was one of the top cities for entrepreneurs and how there were young people like myself doing great things in Oklahoma City, and that was important to me. Something about that entrepreneur thing really got me.”

Anadu accepted Devon’s offer last summer and began looking for housing within walking distance of her new downtown office.

“They thought I was joking when I said I wanted to live within walking distance of work,” Anadu said. “[Devon] finally connected me with a realtor that got it.”

Growth

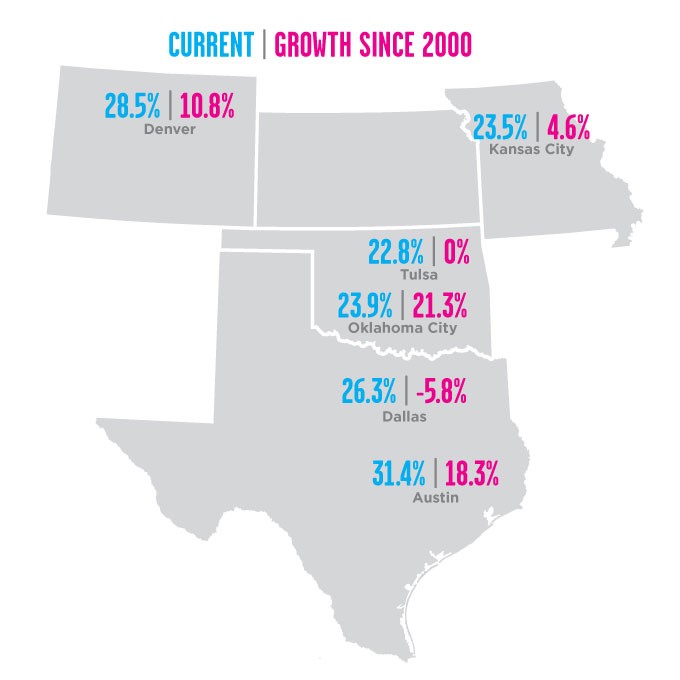

There are numerous ways to track millennial growth, but comparing the number of 20- to 34-year-olds in 2000 with 2013, using Census data, OKC boasted one of the largest regional young adult gains.While the millennial share of OKC’s population — 23.9 percent — is less than Dallas, Denver and Austin, its growth rate since 2000 has outpaced every major city in the region.

Since 2000, its millennial population grew by 21.3 percent, a larger growth rate than Austin (18.3 percent), Denver (10.8 percent) and Dallas (-5.8 percent).

“Over the past five years, I think the culture of our city is kind of catching up to match the appeal of other cities,” said Rachel Hinderman, who moved back to Oklahoma five years ago, after working in New Jersey. “We’ve got more local restaurants and more local shops, and there are a lot of new cool options to be invested in.”

Hinderman, who works for Saxum in OKC, said she believes there is also an appeal to being here because of the low cost of living.

“The economy and the cost of living has always been better here in the Midwest than in other parts of the country,” Hinderman said. “You add in all the changes and it really makes a difference.”

In August, reporter Shaila Dewan highlighted in a piece for The New York Times that the low cost of living in middle America is an attraction for many young adults.

“The country’s fastest-growing cities are now those where housing is more affordable than average, a decisive reversal from the early years of the millennium, when easy credit allowed cities to grow without regard to housing cost and when the fastest-growing cities had housing that was less affordable than the national average,” Dewan wrote. “Among people who have moved long distances, the number of those who cite housing as their primary motivation for doing so has more than doubled since 2007.”

Dewan’s article also highlighted OKC’s 7 percent growth rate since 2006, making it No. 12 on the list of fastest growing cities in the nation.

Keeping talent

While OKC is the state’s creativity and entertainment hub, its low cost of living is not confined to city limits. Affordable housing, at least compared to the national average, is found in its many suburbs. As millennials age, there is concern that the city will lose residents to the suburbs. In fact, OKC’s population of 35- to 45-year-olds has declined by 4.2 percent over the past decade, indicating it has not yet become an attractive place for middle-aged adults and families.“I think the schools could be a huge deterrent for young professionals who might be looking to have kids,” said Dustin Akers, a young professional who moved here from the East Coast three years ago. “That may be what prevents them from staying in urban Oklahoma City.”

Like many urban school systems, Oklahoma City Public Schools battles negative perceptions as it deals with poverty and diversity issues often not found in suburban districts.

“I don’t think we have done what we intended to do, which is move the needle on city schools,” Ward 8 Councilman Pat Ryan said at a council workshop last year. “In my area, there are a lot of new subdivisions being built with signs that read ‘Piedmont Schools’ and ‘Deer Creek Schools,’ but I haven’t seen one sign that says ‘Oklahoma City Schools.’”

The Oklahoma City Council agrees that the school system’s success also will determine the city’s long-term success. City Hall joined forces with the district to help fund after-school programs, student transit and other programs. Momentum also is building around the new superintendent as community leaders say they believe positive change is coming.

The new John Rex Charter Elementary School downtown makes living there more feasible.

“[The school] makes downtown more attractive for families and makes living downtown more of a realistic achievement for families,” said Daniel Chae, PTA secretary at John Rex and a parent of two students.

While OKC has reinvented itself in the past several years, it lacks many other items often found on millennial wish lists.

“I think some of the key neighborhood characteristics that are desirable [are] still lacking,” Akers said. “Walkability and [public] transit are very important.”

OKC has recently increased its investment in sidewalks, and it plans to build a new downtown streetcar system, projects city leaders say are designed to attract young adults. There is also talk about a regional transit plan to help OKC compete with cities like Denver and Dallas, which already have strong regional rail and bus systems.

“I had a pedestrian lifestyle in Denver, a pedestrian lifestyle in Houston and in Brooklyn,” said Anadu, remarking that her new neighborhood downtown is a walkable community. “I think I would be really unhappy and wanting to resign already if I lived where I have to drive.”

Meeting expectations

A growth in millennials results in a need to adapt city services to a new era of technology and collaboration, Cornett said.“We have a new generation of 20-somethings moving to the city with higher expectations of how they communicate with each other and how they are going to communicate with government,” he said. “If we’re going to embrace them and try to help them feel like they are part of the success story, we’ve got to meet them halfway.”

Cornett said the city is examining and harnessing new technology for its younger residents, including a new City Hall mobile app.

Young adults also want a city with quality public transit, according to an April survey by The Rockefeller Foundation. It showed that 54 percent of millennials would consider moving to another city because of better public transit. Sixty-six percent say public transit is a “top three” reason for choosing where to live.

“Young people are the key to advancing innovation and economic competitiveness in our urban areas, and this survey reinforces that cities that don’t invest in effective transportation options stand to lose out in the long-run,” said Michael Myers, a managing director at The Rockefeller Foundation. “As we move from a car-centric model of mobility to a nation that embraces more equitable and sustainable transportation options, millennials are leading the way.”Beyond technology and transit, young adults also have high expectations when it comes to cultural activities, such as music, art and theater.

“Oklahoma City has really taken off,” said Kathryn McGill, who founded Oklahoma Shakespeare in the Park in 1985. “A lot of young people from outside of Oklahoma from larger cities have moved here, and their expectations of what a city should be is different than what Oklahoma City has been.”

OKC’s cultural options have expanded in recent years with new theater groups, art galleries and even the arrival of a new pro sports team, the Oklahoma City Thunder.

A city’s cultural environment also includes local dining options.

“Millennials eat in restaurants far more than non-millennials and spend an average of $21 more per month eating out,” wrote Jeff Fromm of the Millennial Marketing website, referencing a Barkley consulting group survey.

While OKC strives to replicate the cultural offerings and infrastructure of places like New York, Austin and San Francisco, what it lacks in population and endless entertainment options it makes up for with relatively low traffic, affordability and a less intimidating environment for entrepreneurs.

“The diversity of things to do in New York is almost overwhelming,” Anadu said. “But when 30,000 people show up for a food truck [festival] here, clearly there is a thirst here for more stuff to do. But Oklahoma City has its own charm, and that’s cool.”

Print headline: A fresh look, OKC works hard to attract young professionals,and they are changing the city forever.