It all comes down to fear and lives at risk.

For certain American citizens, a hasty or thoughtless gesture, hands hidden in pockets or a vocal pitch rising in uneasiness can lead to the loss of life at the hands of police.

It’s what the American public, especially African-Americans, took away from Ferguson, Missouri, where a white officer shot and killed unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown during the summer of 2014. Months later, 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot and killed by Cleveland police after officers mistook his toy gun for a real weapon. In northeast Oklahoma, a reserve Tulsa County deputy officer allegedly mistook his own gun for a Taser, shooting and killing Eric Courtney Harris during an undercover sting operation just over a year ago.

Most recently, Alton Sterling was fatally shot by police in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The 37-year-old was selling CDs outside a convenience store. A cell phone video showing an officer tackling Sterling and firing shots went viral. A day later, 32-year-old Philando Castile was shot dead by an officer in suburban St. Paul, Minnesota, following a traffic stop. Through streaming video posted to Facebook Live, the world watched the painful event unfold. Police have killed at least 146 black people, five in Oklahoma, since Jan. 1, according to The Counted, an investigative and crowdsourced data project by The Guardian that tracks police killings in the United States.

Following flared tensions over the officer-involved deaths, five law enforcement officers were gunned down July 7 in Dallas and at least three officers were fatally shot July 17 in Baton Rouge, prompting President Barack Obama to urge Americans “to temper our words and open our hearts” in a July 17 address to the nation.

Building trust between police and the communities they serve is no easy task. Racism and its link to alleged police brutality is not unique to the last few years and dates back before the civil rights heyday of the mid- and late-’60s. However, just as powerful reporting, photos and video did in that era, today’s national media coverage mixed with social media engagement have again thrust the conversation of police brutality, racial discrimination and civil rights into the public consciousness. With each unarmed black man or woman killed by police, protests in American cities erupt, posing the questions Can the justice system be color-blind? and What is the future of Black America?

Social change

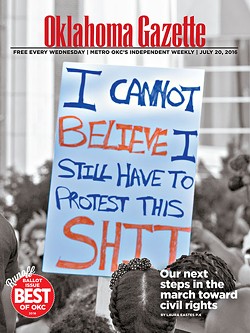

Oklahoma City’s conversation publicly launched July 10 when Black Lives Matter Oklahoma, along with several other civil rights organizations, led marchers over G.E. Finley Bridge and into Bricktown for a peaceful protest, rally and memorial vigil in solidarity with the families and communities impacted by the hundreds of black Americans killed by police across the nation.

“Before the healing begins, we must diagnose then treat what ills us in this country,” Grace Franklin, executive director of OKC Artists for Justice, told the crowd amid cheers and chants. “We are plagued by racial and socio-economic discrimination manifested in the belief that black lives don’t matter as much as other lives when they are interacting with the police. Somehow, black and brown lives are void of families, dignity, love and humanity. That is unacceptable.”

The march, rally and protest event is believed to be one of the largest civil rights demonstrations in Oklahoma City since the 1960s.

“This was a call to action,” Rev. T. Sheri Dickerson, a Black Lives Matter Oklahoma event organizer, told Oklahoma Gazette. “Action is something we needed. We can’t be successful and we can’t continue unless we have everyone involved.”

Oklahoma City’s protest, fueled by anger, frustration and grief over recent fatal police-involved shootings, is shaping up to serve as a crucial stepping-stone in the next phase of civil rights in the state, sparking further public course.

“We will start those uncomfortable conversations,” Dickerson said while discussing planned Black Lives Matter Oklahoma and OKC Artists for Justice town hall meetings between the public, law enforcement and community leaders beginning later this month. “The [forums] have to bridge the gap to help deescalate and defuse the tension between the community and law enforcement officers.”

Over the weekend, the NAACP, the People’s Economic Opportunities for Prosperity, Longevity and Equality Foundation (PEOPLE) and Midwest City police knocked on doors in Midwest City’s Quail Ridge housing addition to encourage community engagement and build relationships with law enforcement. July 28, the same area will be the location of a march against violence.

Saturday, nonprofit Believe Inc. hosts It’s A Community Thing, a march to raise awareness around issues of community violence, incarceration, poor health outcomes and mental illness. The march begins 9 a.m. on the steps of the state Capitol.

“It is mandatory that we get involved and we raise our voices,” said Garland Pruitt, NAACP Oklahoma City president. “Change needs to happen. If we don’t confront it, it won’t change itself.”

Civic participation

Gazing out into the distance, former state Sen. Connie Johnson was taken back at the sight coming over G.E. Finley Bridge on July 10.

The first row of more than a dozen Black Lives Matter Oklahoma marchers locked their arms as they lead hundreds who held up signs calling for an end to civil rights injustices and police brutality.

A year earlier, Johnson marched across Selma, Alabama’s Edmund Pettus Bridge to commemorate the historic and brutal 1965 civil rights march that widely became known as Bloody Sunday. She knew from personal experience the significance of marching in solidarity to end violence and push for equality.

“To see that replicated in Oklahoma City in this moment, that’s what struck me,” Johnson said. “We are on the forefront of a revolution of people starting to see they can make a difference.”

Johnson has long advocated for civic engagement and voting in local, state and national elections. She believes civic participation and the voting booth are essential to addressing policies regarding officer body cameras, excessive force, civil rights and other issues chanted by the crowd.

“The only way you change the policies is if you change the people,” Johnson said. “We have to hold our elected officials accountable.”

Police accountability

Ward 7 Councilman John Pettis Jr. often hears from constituents who question the large number of white officers patrolling northeast Oklahoma City.

“My response is always, ‘Yes, this is true,’” said Pettis, whose ward includes the city’s largest concentration of black community members. “We, as African-Americans and minorities, must get more people involved in law enforcement.”

About 10 percent of the Oklahoma City Police Department (OKCPD) is African-American, Pettis said. Recent efforts, such as the Metro Tech Pre-Law Enforcement program — a partnership with the OKCPD — have resulted in minorities and women pursuing entry into the force. Pettis is the council’s leading supporter for the pre-law enforcement program. He said more support is needed if the community wants to see a more diverse police force.

“As we complain about not having enough black officers, we are not pushing our own children to be police officers,” said Pettis, whose niece is participating in the program. “If we encourage kids to be NBA or football players, we should also encourage them to go into law enforcement. That’s the only way we will be able to change the dynamics of the police department.”

Last fall, OKCPD began testing officer body cameras after the Oklahoma City Council approved the purchase in hope of reinforcing public trust in law enforcement. Their use was suspended in mid-June following an arbitrator ordering the program on hold until the police union and department reach a policy agreement.

While citizens wait to see officer-worn body cameras again, Pettis advises another avenue for ensuring the accountability of police officers. The councilman would like to see the public request more frequent officer ridealongs.

“The community can see what the police officer sees every single day,” Pettis said. “It allows an officer to learn about the community. Wouldn’t it be awesome if we had a month when community members did police ridealongs on all shifts in the Springlake division? What kind of message would that send?”

Bystanders’ role

Too many high-profile incidents of police brutality and shootings have compelled bystanders to pull out cell phone cameras and record interactions. The footage often plays an important role in investigations as well as public awareness of possible police misconduct.

American Civil Liberties Union’s Mobile Justice app enables witnesses to submit videos and details of potentially troubling law enforcement actions to Oklahoma’s ACLU office.

“The ACLU developed this app in response to what we see as an epidemic: racial profiling, over policing and overreaching of law enforcement in many communities, but especially in communities of color,” said Allie Shinn, ACLU of Oklahoma spokeswoman. “If you are having a negative or potentially negative interaction with law enforcement, you can’t call the police on the police. Your only option is to document the encounter and get some help later.”

Staff reviews submissions and ACLU’s legal team takes action where potential legal remedies exist. As of July 13, more than 900 people have downloaded app, Shinn said.

Marching on

Black Lives Matter Oklahoma attracted thousands of supporters, including a handful of local and state lawmakers, but many hope the message spreads beyond the estimated 2,500 people who gathered in Bricktown July 10 for the event.

“Not only do the people need to take it to heart — what it replicated and what it stood for — but the elected officials need to, too,” Johnson said. “In this moment, we have an opportunity to listen and be earnest in our response as public servants and actually do something.”

Pruitt said he was encouraged by the passion for change ignited in the youth and young adults who participated in the protest. He believes real change will come when participation in rallies, elections and encounters with policy makers increases.

“If we don’t have conversations, we don’t have anything,” he said. “It is real easy to go on Twitter and Facebook, but if you are not meeting with the people that make decisions, draft polices and vote on the laws, you haven’t accomplished anything.

“As long as we live and breathe, we have got to stand up, speak up and confront those situations. We all have a voice, and we need to use it.”

Charting a course for change takes resources and knowledge of the justice system and government. Black Lives Matter Oklahoma set the public on course during the July protest. Upcoming events will keep the public focused as the longer march continues.

“We will extend ourselves to law enforcement. We understand, appreciate and honor their sacrifice given on a daily basis, but let’s get to know one another,” Dickerson said. “Once that type of understanding is accomplished, Black Lives Matter will focus on the community and the progression of the people. No longer will we speak out because there has been another life loss unnecessarily from excessive use of force, abuse of power or out of fear.”

Print Headline: Marching forward, Following this month’s Black Lives Matter Oklahoma march, rally and protest, the community relays an urgent need to take action and improve relationships.