On the second floor of a downtown courthouse that has witnessed nearly 80 years of growth, destruction and more growth all around it, a councilman’s lawsuit to stop the demolition of an old bus station is simply a tantalizing headline.

The real story might be about the growing pains of Oklahoma City’s urban core as competing interests look to shape its infrastructure for the next generation.

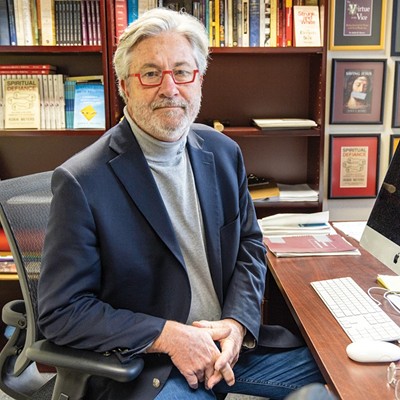

“One person’s view of progress is Houston, Texas. Another person’s view of what is progress could be somewhere in Maine,” said Oklahoma County District Judge Roger Stuart following a two-day trial over City Councilman Ed Shadid’s attempt to save Union Bus Station. “This story is not a unique story about someone who views progress as different from somebody else. I, for one, am grateful that [Shadid] has raised this issue.”

Stuart, who is expected to offer a verdict within the next two weeks, also said he is limited in what he can do to halt the demolition, especially if the city ordinance is clear, as lawyers for the city and 499 Sheridan, the development proposed to replace the bus station, have argued.

But whether or not Union Bus Station is replaced with a mixed-use high-rise and parking garage or whether OKC will follow the lead of cities like Savannah, Georgia, which have turned similar venues into popular restaurants, the larger question remains: What should downtown Oklahoma City look like?

“Part of this case is that the Downtown Design Review Committee’s [DDRC] guideline and criteria for determining demolition isn’t very specific and there’s a lot of additional information that is sometimes presented and sometimes is not,” said Aubrey Hammontree, Oklahoma City’s planning director. “We have been working on this for four years, trying to strengthen the ordinance.”

One of Shadid’s arguments is that the demolition approval process regarding historic buildings is flawed. He believes the city will ultimately adjust this process to allow more time to present plans that could help save historic structures such as Union Bus Station.

“I thought the evidence [to save it] was never really presented back in December to the DDRC,” Shadid said. “It’s unfortunate that it takes this expense and time of going to court to get the level of discourse that we should have seen in December.”

The case

When developers of the proposed 499 Sheridan project — expected to house offices for Devon Energy and other tenants — approached the Downtown Design Review Committee in December, they asserted that the station was “beyond repair” and the expense of moving the proposed construction to another location would be prohibitive.

Hammontree’s department made a recommendation to save the station, but the DDRC approved the demolition request.

Demolition opponents said the city was removing its few remaining historic structures, and in March, Shadid filed a lawsuit claiming the DDRC failed to follow the city ordinance, which, he argued, requires the group to consider a structure’s historical value before approving or rejecting demolition plans.

Shadid’s opponents, including lawyers for the developer, implied he might be a rogue councilman looking to delay a project with ties to a corporation — Devon Energy — he might unfavorably view.

Shadid’s fellow council members voted to fight back, and last week’s trial in Oklahoma County court served as the stage for this conflict.

“The bus station really doesn’t [have historical significance],” said attorney Joe Bocock, who represents the 499 Sheridan developer, in his opening statement to the judge. “It’s just not architecturally significant.”

A movement

Though he is the council’s lone advocate for preservation of the bus station, Shadid hired an architect to create an alternative development plan that preserved the building.

Even the DDRC hearing in December featured just two opposition statements, which gave the appearance that most of the community agreed with 499 Sheridan development plans.

However, reaction on social media platforms showed stark opposition to demolition, especially among young adults.

“Likes” and retweets have little power against political persuasion.

At the December DDRC hearing, Allison Bailey spoke out against the demolition plan and said there were many more like her who felt the same way.

“There were a lot of people who voiced a frustration the same as mine on Twitter,” Bailey said. “But I don’t think a lot of those people sent an email to the DDRC or the city manager’s office. I think we see the same issue at play in voter turnout.”

Bailey said part of the challenge her generation faces is how to get more involved in the civic process by volunteering for various boards and contacting elected officials.

Bailey and others argue that the proposed 499 Sheridan development will stifle nightlife and other quality-of-life features that residents look for when considering a move downtown. But while the online arena echoes Bailey’s beliefs, in the traditional halls of government, where developers and lawyers understandably focus on the bottom line, a competing narrative is harder to find.

The Skirvin

Attorney David Box, who spoke in favor of the demolition, held up a 1950s aerial photo of downtown, which also was a piece of evidence Shadid’s team used to show just how few of those buildings still exist.

“When we look at this image, it might seem dark and sad that these buildings are gone. But if we really focus on what the image represents, this block right here, where all these buildings are gone, now stands the Devon Energy Center,” Box said during last week’s closing court argument. “I would submit that what stands there now is a much greater scenario for this city than this group of buildings [from the past].”

He then pointed to the spot where Chesapeake Energy Arena now stands.

“This block right here,” he said, “what it represents now is the home of the first professional sports franchise in this city’s history. I would submit that what we have now is better than what these buildings may have been.”

Shadid’s legal team said historic preservation has enhanced other projects, such as the Skirvin Hilton Hotel, which is more than 100 years old and was successfully restored a decade ago.

Box disagreed with the comparison.

“This is not the Skirvin Hotel,” he quipped.

Over the past few decades, for each saved Skirvin, there seems to be a lost Stage Center. However, unlike urban renewal attempts of the ’60s and ’70s (such as The Pei Plan), recent destruction of structures is followed by the construction of glossy towers.

On the block along the former Stage Center site, four high-rise towers including condominiums and a new headquarters for Oklahoma Gas & Electric are planned. One block over is Devon Energy Center.

The addition of a convention center and the 499 Sheridan development will inject vitality into the area that it lacked just 20 years ago, but it also will sever many of the city’s structural and visual ties to its past.

There is no consensus on which might be healthier for the city — new skyscrapers or a renovated older building with character and history — but Hammontree said successful downtown growth incorporates competing thoughts, visions and developments.

“It means everybody is interested in the [future of downtown],” she said about the court case. “And that’s not a bad thing.”

Open discussion

As Shadid waits for the verdict in a case he admits is a long shot, he refers to his effort as partly successful.

“I think there is more than one way to win, and I think we have already won,” Shadid said. “The goal of Devon and the developers was to ... spring this on the public in the middle of December, 10 days before Christmas, get it heard and start the demolition quickly. We have been able to have an additional six months of discussion and reflection on what type of city we want to live in going forward. That’s a victory.”

Developer rights were a major theme of the case, as lawyers for 499 Sheridan said the city had no right to tell a business how to build a building in downtown as long as it followed city ordinances.

Shadid disagreed.

“The taxpayers have invested so much money in the public infrastructure around [downtown], so to some extent, the public does have a little more right to be a partner in this development,” he said. “[The developer] can argue that they’re not taking taxpayer funds through this development, but the truth is the taxpayers are putting $130 million in a streetcar that goes to their front door, there are Project 180 improvements, there are the Myriad Garden improvements and so many other investments by the taxpayers.

“If you want to do something out in the suburbs on empty land, we could[n’t] care less; do what you want. ... But if you are going to demolish the last intact grouping of historic buildings [downtown], there is going to be a loss to society. Society is giving up something, so there has to be a balance.”

Print headline: Defining progress, As the city makes more room for new development and long-term growth, some wonder if it’s also destroying its vibrant history.